Written contribution to For Inclusion in the Syllabi, an exhibition I curated as part of curatorial collective FSP. The full publication is available to download from the FSP website.

On Being a Shadow of a Shadow

One.

She is clambering hurriedly through the bramble and ankle-short grass. The undergrowth is thick, a clumsy hindrance. Fast approaching the river, she doesn’t look back. She is breathing heavily. If nymphs breathe that is? Perhaps they don’t possess the drafty, moist and internalised pipe system that allows humans to inhale/exhale. Maybe their breath originates somewhere other than in the organs, (that act as an organ), that produce voice. Birds apparently derive their singing from her, so I assume her voice must be a sort of master template of all voices, a voice that comes from somewhere that just is.

He is following her - determined expression, quick and aggressive pace, following her by her sounds, the voice originator. His dark longing is written in his face, arms extending invisibly forwards to touch her. Through a perverse perseverance he charges on.

She reaches the riverbank, and here it becomes unclear. When imagining the transformative act, I have been seeing it as a set of before and after images such as the ones in advertisements for diet pills or hair implants. Before: Nymph. Supernatural. Beautiful, but with a worried expression on her face. Probably naked and probably plump - Rubenesque as they say. Trapped in a half-stiff painterly motion. After: Water reed. Flora. Half submerged in water and either drowning in its newfound shape or confidently swaying and whispering in the breeze. The specifics of the metamorphosis hence remain blurry. Does she evaporate into smoke like a magic trick and re-materialise into water reeds when the smoke hits the water? Or does it happen more like a dramatic chemical reaction such as the ones science teachers produce for distracted hormonal minds with bangs, fizzes and vile smells? Maybe, in the style of a comic superhero, she is squashed, pulled and squeezed into an elongated mush of deformed atoms and from this restructures into a vegetative entity. Or perhaps words were simply spoken and with that she was reformulated.

Specifics aside, the story follows that Pan reaches the riverbank after the transformation has taken place. In utter frustration and despair he commits an act of destructive creativity as he cuts the water reeds from their roots and with them produces the world’s first wind instrument, the pan flute. He proceeds to lament his loss with a melody. The former nymph now pan flute, acts as a translationary object of his bewailing. It is the only way he can evoke her, though he knows that for every note played he is freeing her bit by bit from her entrapment as it allows her to change shape yet again, into musical scores released into the ether. I’d like to think Syrinx is invoked every time someone plays the flute, when breath becomes notes become air. Every song played is a shadow of a former made. Thus she is fading, or rather transforming, her story owned not by words, but told through music, open for (re-)interpretation.

Two.

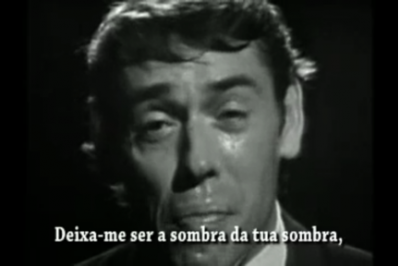

An oblong face appears out of the dark, closely cropped, in shades of black and grey, pearls of perspiration congregating on his upper lip, chin and forehead. Jaques Brel is looking straight at us, showing no apprehension for the resulting intimacy, which is only subdued by the surface of the computer screen and the silently screaming ad clutter of youtube.com. Not deterred by the discomfort of the sweat-inducingly hot studio, the gaze of the camera lens and the invisible but audible audience upon him, Brel has something to say - in song. His face is distorted with regret, it seems his appeal comes from the very bottom of his being:

Ne me quitte pas.

Ne me quitte pas.

Ne me quitte pas.

Don’t leave me.

Noone left him, we as viewers especially, transfixed as we are by his face, his sweat blending in with his tears (or is it just sweat? No, I want to be convinced by his acting), his teeth. She didn’t leave him either. Brel left her, his mistress, when she became pregnant with their child. Still, on that day in 1959 he records a song that asks her to take him back - back to a place where there is no pain, away from the rain, to a kingdom of love where she will be queen. He deserves the hurt he now contains - he endures it, embraces it. Wrenching the words out of his vocal folds, one after another they string together to form a damning but tender ode to what he once called ‘the cowardice of men’.

Ne me quitte pas.

Ne me quitte pas.

Ne me quitte pas.

Don’t leave me.

Brel, a Belgian, recorded ‘Ne me quitte pas’ in both French and his native Flemish. Wikipedia counts over ninety cover versions of the song in over twenty-three languages. Reiterated across the decades, Brel’s plea has become caught in a series of revisions and translations. It has become a symbol for both regretful and mistreated lovers, as his spectre is relentlessly summoned up to speak for them. As his repentant message echoes through this outspread multilingual choir, his face on the screen is being watched again and again. She has now become a shadow of him - he a ghost of them.

It is enough being the shadow of your shadow.

The shadow of your hand.

The shadow of your man.

Ne me quitte pas.

Ne me quitte pas.

Ne me quitte pas.

Don’t leave me.

Three.

For Inclusion in the Syllabi houses three works by Martijn in’t Veld:

Untitled | 2011 | Printed poster

Melody: A guitar pick on a shelf in a room in a building in a city in a country on a planet in a space | 2011 | Guitar pick

Biography | 2011 | A copy of 'Felix Gonzalez-Torres' by Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Nancy Spector, Guggenheim Musseum, 2007, borrowed from the Willem de Kooning Academy Library in Rotterdam for the duration of the exhibition